We worked with adolescent girls to design their own reproductive health sessions. Here's what they taught us.

I'm on my way to Zaatari Camp today, a place I've been spending much of my time since the launch of WISE Girls — a project that empowers girls to design and facilitate their own sexual and reproductive health sessions.

This project is very close to my heart. It's been so inspiring to watch adolescent girls take the lead in designing their own space to have open and honest conversations around their reproductive health. When you work in the humanitarian field, you need something to ground you, to make you remember the value of the work you do.

WISE Girls is what grounds me — being around the adolescent girls I work with, and remembering the adolescent girl who still lives in me.

I've been reflecting a lot lately on how society perceives girls before and after they reach puberty and also how we, as women, perceive ourselves. The pressures of living up to society's expectations are real and strong — so strong that we internalise them, sometimes without even realising. This can manifest itself as a lack of confidence and shame, especially when it comes to our bodies. It creates a weight on our shoulders that can drag us down.

I not only recognise this in myself, but I also see it in the girls. I can relate fully to the girl who told me, "When we are young we wear what we like and play, but when we get older we dress differently and do not go out." Women need solidarity with other women, and spaces where they can reclaim their agency and break down power dynamics.

WISE Girls has been an incredible example of this. We wanted to hear directly from the girls about what topics they wanted to discuss and how they wanted to do it. So we sat with them on the ground and chatted about their relationships with their bodies, how they understand the changes that happen to them and what they would like to learn. We also talked with caregivers and community members, which allowed us to get closer to understanding the needs of the community.

From multiple conversations, we learned that tweens usually learn about their bodies from older adolescents. And that became the basis for our programme.

We gave the older adolescent girls some crafting materials and a challenge: create something that will help you explain puberty to a tween. The girls created a dollhouse, a puppet show, a board game, a story, and a play.

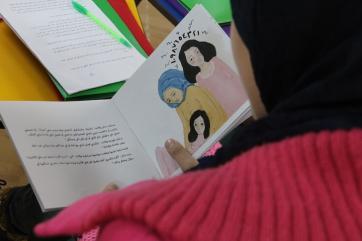

What we noticed was that storytelling was present in every idea. Eventually, we settled on a storybook called Jazeeret el Zohoor, or "The Island of Flowers." The title borrows from a phrase one of the mothers gave us: when a girl hits puberty in Syria, she said, "we say she bloomed."

Because our inspiration sessions taught us that tweens usually learn about their bodies from their older friends or sisters, it was clear the girls had to lead the sessions themselves. The dynamics among the girls has been inspiring to watch. They encourage each other to get out of their comfort zones, they aren't afraid to ask questions, they laugh, and they look away when they're shy. They are able to share all their emotions because of the safe space they created.

This programme is in partnership with IDEO.org, who is leading the way in human-centred design. The special thing about a donor and design partner like IDEO is the flexibility to adapt, knowing that solutions are not black and white, and sometimes you need to dance in the gray. This is also how I've come to see the girls, and myself.

I often get asked about how adolescents can lead programming, and I think about an older girl in the programme, Raw'a. She held the storybook in her hands, crossing out some words and moving others around. Not only did she feel as though the story was hers to modify and edit, but in a way she was resisting the authority of what's written in the book, questioning it and making it relevant for herself and the other girls.

It's moments like these that I'm reminded of the reasons we wanted this programme to be girl-led. The girls in Zaatari know each other better than we or any outsider will ever know them. They value each other's advice, listen to each other, and trust each other.

What I've learned from human-centred design is that nothing is perfect. We are making mistakes and the girls are making mistakes, but we are trying. I know this project won't change the world. The girls will still carry the burden of being females on their shoulders. They'll face the expectations that come with puberty, and they'll feel helpless at times. These problems are systematic and bigger than what Jazeerat Al Zuhoor can do.

However, flowers will definitely bloom along this journey. And if we, and Jazeerat Al Zuhoor, can make the girls feel even a little bit less alone, we will have succeeded.

---

Ayah Al-Oballi is a Senior Officer for the Regional Centre for the Advancement of Adolescent Girls, Mercy Corps' knowledge and innovation hub that aims to put adolescent girls in the centre of programming. This article was co-written with Jana Qazzaz, Communications Intern. This partnership was funded by DFID.