The Wages of War: How are Syrians adapting their lives to the crisis?

This story is part of our special series, 7 for 7: Seven voices for seven years of the Syria crisis. View the complete series here ▸

The scale of death and suffering in Syria is monumental. What began as a peaceful protest in 2011 has spiraled into a humanitarian crisis unprecedented for our modern times: The war has killed as many as 400,000 Syrians and displaced 11 million more. The crisis has set Syria’s development back nearly four decades.

Yet, despite these immense challenges, Mercy Corps’ work in Syria has found that some households are managing the devastating impacts of war better than others. Our new paper, The Wages of War, explores how these Syrian households have been able to adapt to new lines of work that allow them to support their families amid crisis.

Read more below in this interview with researcher Vaidehi Krishnan of Mercy Corps' research and learning team, or view the full paper here.

How did this research originate?

I joined the Syria response in 2015, and even as far back as then, in the midst of the conflict, we were hearing stories of farmers who’d always grown wheat all their lives switching to coriander because they found out coriander was faster and easier to sell. Then we started hearing stories from other locations where some people had found jobs in a new sector—maybe they worked for a cell phone company or found a new way to harvest tomatoes and were sharing information with their friends and extended community.

We were seeing a shift in how Syrians were behaving during the conflict. It was surprising for us because we had never formally studied whether people change the way they live their lives during conflict. How people continue to provide for their families became an extremely important learning element for us.

We know how people live before and after conflict — we can go in after a conflict is over and support them — but during a conflict, it’s almost unimaginable how people have found ways to feed and shelter their families. So for us the questions became, can people really find another job to support their families, and is it only happening in certain locations, or is it widespread in Syria?

It really became a gut-check. We’re seven years into the conflict, and the major way we support Syrians is with food. But if people are shifting and finding jobs, then what can we as humanitarian workers learn from this and what can we do differently? This was a chance to step back and learn from what’s happening and from the people we work with.

If people are shifting and finding jobs, then what can we as humanitarian workers learn from this and what can we do differently?

Was this happening in communities facing conflict, or just those away from fighting?

We did this research last year, and as of last year, the conflict was pretty widespread in all of Syria. All of these locations inside Syria were still facing some level of conflict. We primarily looked at communities in the north, northeast, and south-central.

We tried to talk to as many representative communities as possible. One reason was to understand, are people shifting their jobs, and is it only happening in locations that are relatively stable, or is it also happening in locations where conflict is active and they’re facing violence every day? So we did it pretty much all over Syria. We chose 120 communities in these three geographies where we were able to find local partners to conduct these interviews.

What's different about Syria now than at the six-year mark a year ago?

I almost want to say everything and nothing. Every year that has passed in the Syria conflict, it has always seemed to surprise us with how the conflict has shifted gears. In January, I read an article asking if this is the year peace will finally come to Syria. As of 2017, the focus was on ISIS-controlled areas, and pushing ISIS out. Conflict was still taking place, but the thought was that 2018 would be the year the conflict would end. But over the last few weeks, we’re seeing pockets of intensified violence.

It’s difficult to say what’s different between the six and seven-year mark. As humanitarian workers, it’s increasingly frustrating. The stability we’re waiting for to help people rebuild their livelihoods is not here today. We’re recognizing as humanitarians that we’re providing people with much-needed food, shelter and help, but maybe there are other things we can do while we wait for stability to come. For the Syrian people, there’s no end in sight. So are there ways we can pivot our work to reach people where they are now?

Did you learn anything surprising?

Much of what we learned in this research was initially very surprising. But as we began reading through the research, a lot of the responses are quite logical. We just hadn’t expected this to be happening in an active conflict zone.

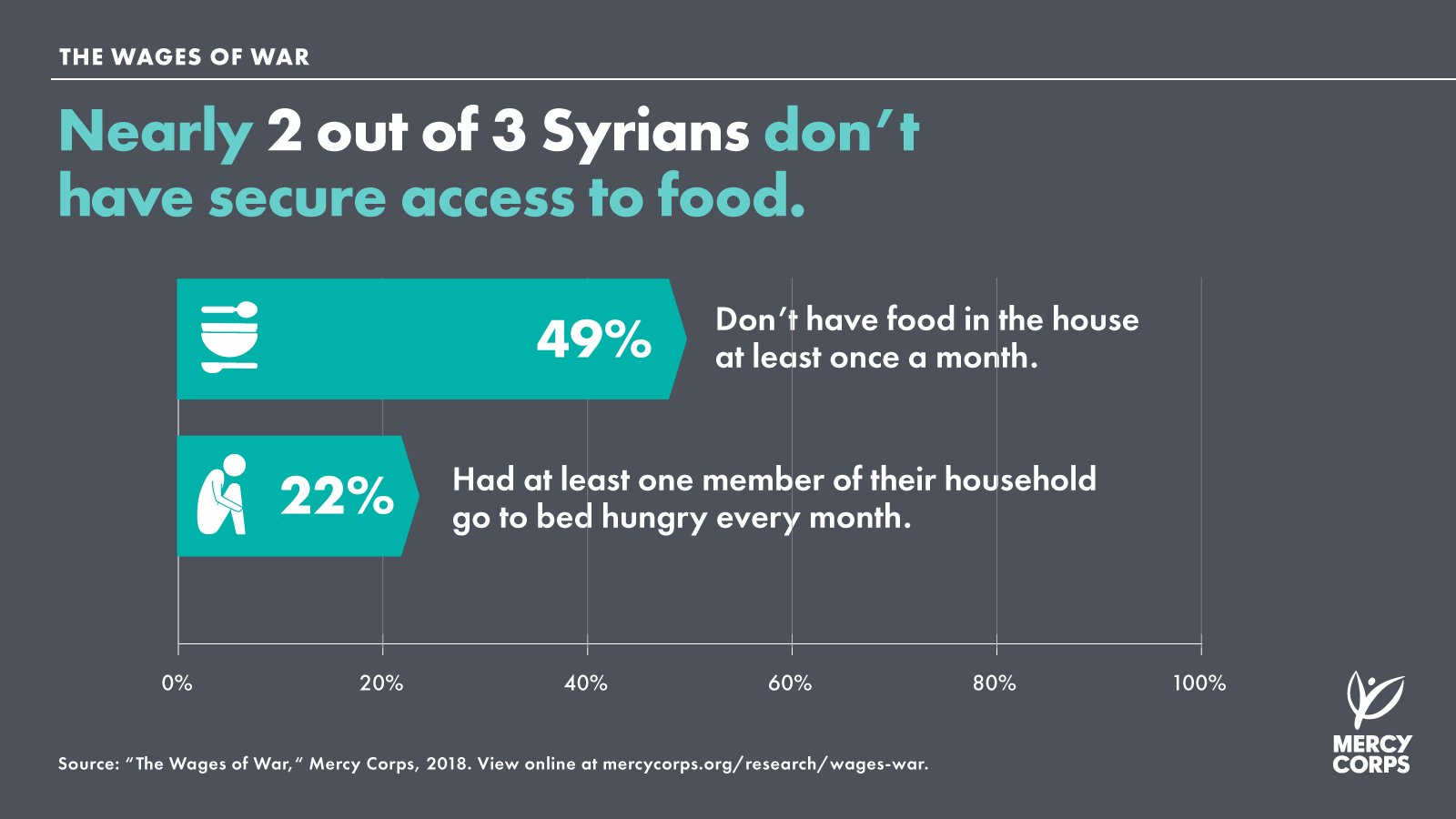

It seems weird to be talking about changing jobs and building livelihoods when the news we see is around bombs dropping—and that violence is happening and it’s extremely important for us to recognize that it is happening. But in the midst of this, what we found is that 1 in 3 households has managed to find a new job. That’s not just farmers shifting from wheat to coriander; we’re talking about someone who has been a farmer all his life is now an electrician, or someone who has been a teacher all her life has opened a retail store. It’s an entire shift in a job.

If any of us has tried that, it’s an extremely important life change. It took me six months when I wanted to change from the private sector to the humanitarian field. And we’re talking about people in the midst of a conflict, where the environment they live in changes every day. They don’t know where the next bomb is coming from or where the next attack is. Yet these people have still found ways to ask, what do I need to provide for my family? What skills are needed in my community? And they’ve found ways to shift to those jobs.

But it’s important to remember this is only 1 in 3 households. Two-thirds of them haven’t managed to do this. So what can we learn from how they’ve adapted to create the same conditions for the others?

In the midst of the violence, what we found is that 1 in 3 households has managed to find a new job.

So what is needed for that other two-thirds of Syrians?

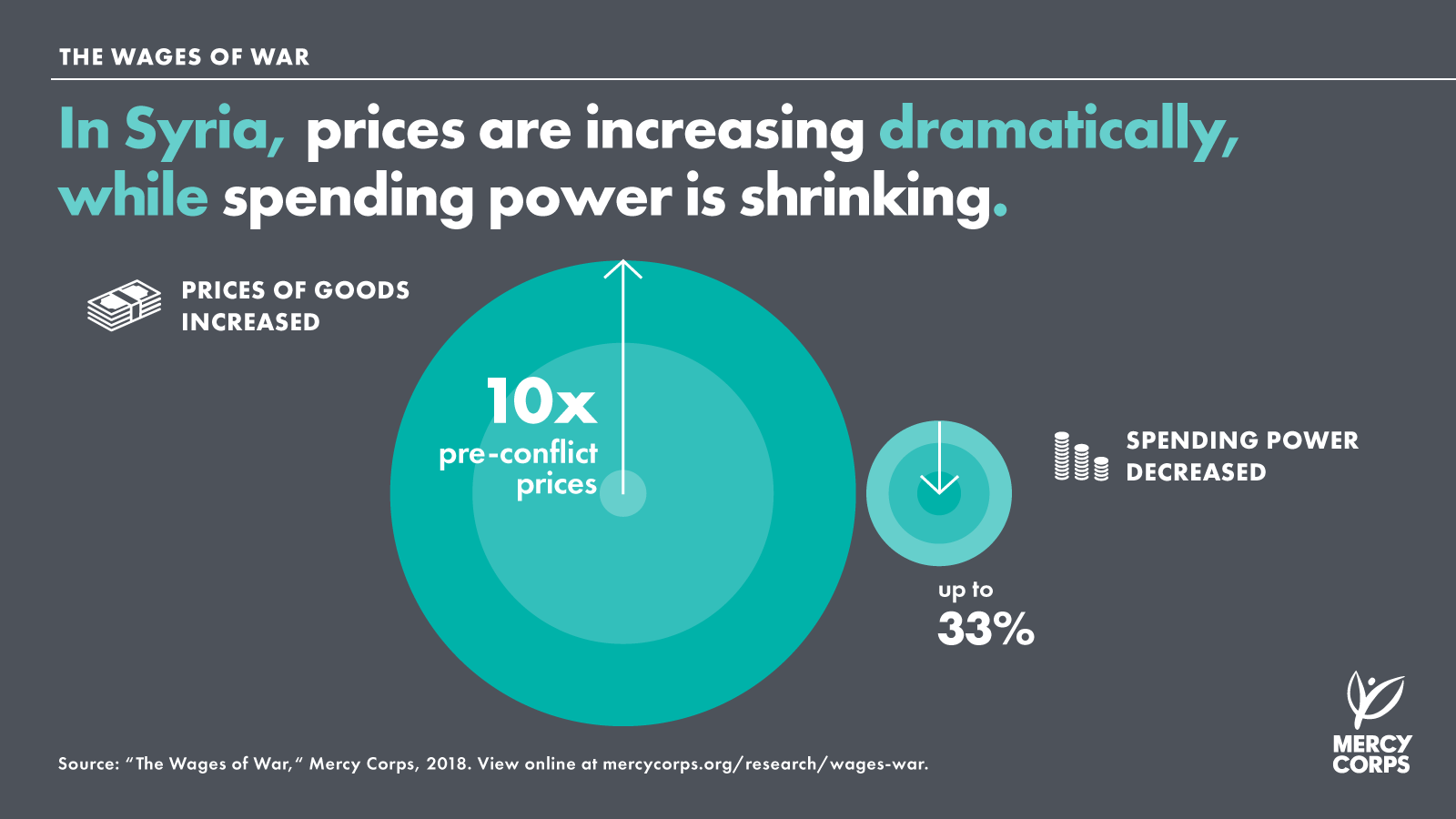

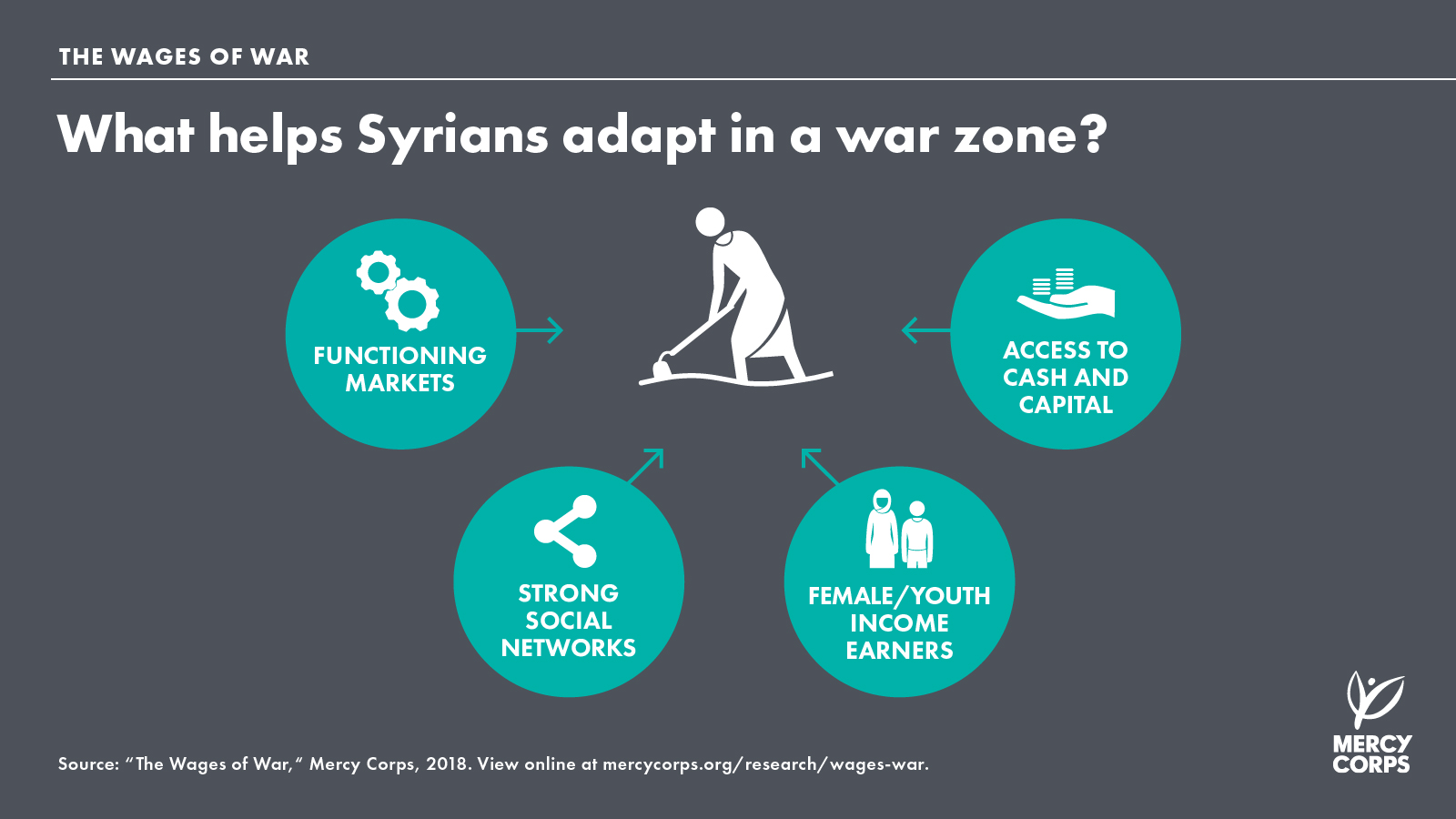

It’s an interesting question, because a lot of the same stuff we were finding to help Syrians adapt is the same things we would need. What is helping people find a new job? The first thing is the ability of an economic market to meet their needs — the ability to get a loan, for instance, or sell raw materials to a business.

When we say market functionality, what we mean is that it’s not just that the markets have been able to provide the food, shelter or water Syrians need; it also means these markets have expanded to create new jobs so Syrians can find a new job in these markets to support their households. Markets have an extremely important effect on whether people can adapt to a new job or not.

What is helping people find a new job? The first thing is the ability of a market to meet their needs.

The second thing that helps people are their social networks. This is extremely important. When I was trying to find a new job, the first people I reached out to were my friends and family, or the people I knew who had shifted successfully into the sector I wanted to enter. I would ask them, what did you do? Where did you find information? How did you do it? This is what Syrians are doing. They’re using technology like you and me, they’re using WhatsApp, they’re reaching out to friends and family to say, “What did you do to change? I heard you were working with Abu Mohammed in his electrician’s shop, and you used to be a tailor.” They’re using their social networks to access social information like you and me.

They’re also using their social networks to borrow money, and to learn a new skill. Most of the people we talked to, we asked them why they borrowed money. It wasn’t just to feed their families; it was to invest in skills development to find new jobs to continue to feed their families.

Syria needs peace foremost — but what comes after?

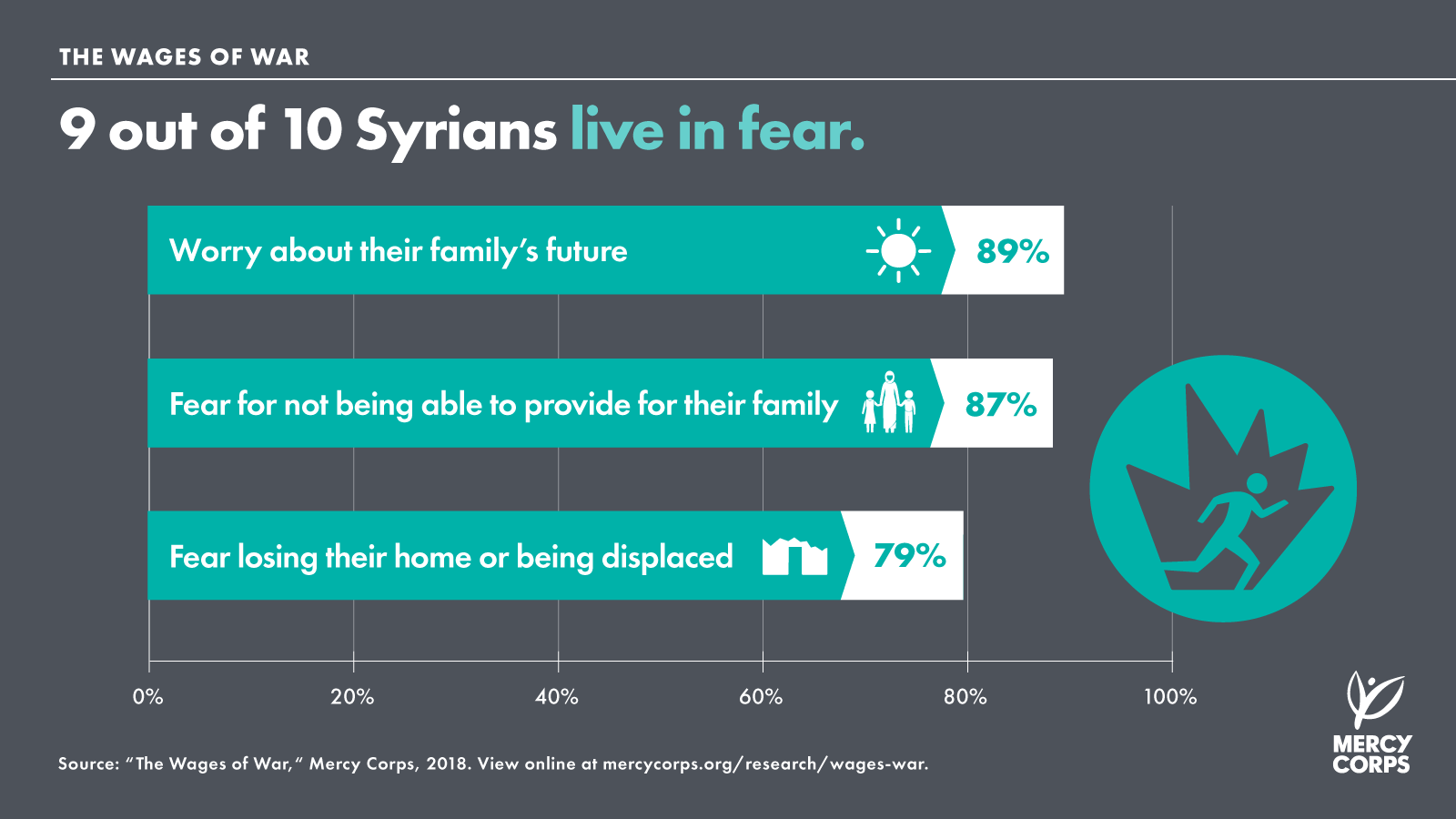

Over the last seven years, we’ve read about hundreds of thousands of people being killed, millions of people displaced, and at some point those numbers start to stump us. We don’t know what we can do or how we can relate. But what this research did for me was to say that there’s no difference between a Syrian person and myself.

They want the same things for their families I would. I want to protect and feed my family. I want a life with dignity. I want a little control over my life. Especially, when you think about Syrians, when you live with so much uncertainty and you don’t know where the next conflict will happen, the least you want is to make a decision over what your household will eat.

What this research did for me was to say that there’s no difference between a Syrian person and myself.

They want to use cash to make the decision about what their household eats today. They want to make that decision. They want to learn a new skill to find a job so they can better protect their family without our support.

When we talk about resilience in the sector, it can be hard to explain. But I like to think of it like a bounceback effect: when you throw a ball on the ground, it bounces back to you. Syrians’ ability to bounce back is eye-opening. What they want for their household is what you and I want, and they’ve been able to do it while living in a situation where they don’t know where the next conflict is going to be or where the next bomb is going to drop.

Does this research reveal any sort of path for how Syria's people might rebuild once the country finds peace?

In a lot of ways, we shouldn’t wait for peace to come. That peace is an important step to solidify what we’re doing, but we need to start changing how we think about providing aid today. If we’re finding that 1 in 3 households can shift their job to better feed and clothe their family, why should we wait for peace to come to change how we would reach them? We need to start now by changing how we provide aid.

As much as we try as humanitarian organizations, our access in Syria is very sporadic. It’s not consistent. When we have sporadic access into these locations, we need to make sure we’re doing the right thing. We need to make sure the aid makes a difference. That means engaging people. Giving them dignity and self-fulfillment when they’ve found a job is extremely important.

We talked to women and young people that never worked before the conflict and who are now the main income earners for their families. A lot of young people were in university, and women in many parts of the country traditionally weren’t the main income earners. These people, new income earners, are telling us they feel self-reliance, self-esteem, and that they feel more positively about their communities.

In a post-conflict situation, it’s extremely important not just that people are able to support their own families, but that they also engage in rebuilding their own communities. Not just the physical infrastructure — that’s completely separate — I’m talking about healing the wounds left from war. It’s extremely important that people are able to come together and heal. This research is one path to engaging people to get there.

This story is part of our special series, 7 for 7: Seven voices for seven years of the Syria crisis. View the complete series here ▸