What we're doing to help end global hunger

Food is central to human well-being: it provides the body with nourishment, offers livelihoods that lift people out of poverty, and brings communities together. Although food is a basic human need, too many people are trapped in a cycle of hunger by forces beyond their immediate control, like poverty, disaster, conflict and inequality.

Despite decades of progress in reducing world hunger, 2017 saw increases in the number of people who are hungry. More than 820 million people still go to bed hungry every night — that’s one in every nine people who don’t have the food they need to live a healthy, productive life.

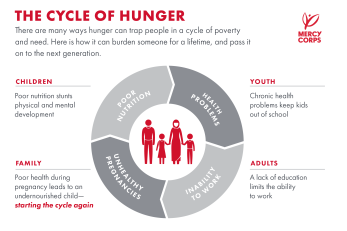

The World Health Organization considers this to be the single greatest threat to global health. Hunger is cyclical and generational: it inhibits people’s ability to work and learn to their fullest potential, which can curb their future and trap them and their families in more poverty — and more hunger.

Mercy Corps takes a multi-pronged approach to helping end world hunger, including implementing programmes that tackle the multiple drivers of food security, while also engaging in policy discussions that influence our programmes. Learn about this work and what is being done to stop world hunger below.

Global hunger today

Common causes of hunger

World hunger is caused by so much more than a shortage of food. Even in places where food is plentiful or can be grown, challenges like disasters, conflict or poverty prevent people from accessing it.

People in poverty generally spend between 60 and 80 percent of their income on food, which can force them to prioritise feeding their families over meeting other basic needs or reaching long-term goals, like sending their children to school. If an emergency strikes, they may need to skip meals in order to cope financially — and the cycle of hunger continues.

According to the Food Security Information Network, conflict and insecurity were primary drivers of food insecurity in 2017, alone accountable for putting 74 million people in need of urgent assistance. Climate change is also eroding existing efforts to improve food security.

Hunger can also stem from inadequate food systems, like a lack of road infrastructure to connect people to markets, or poor storage facilities, through which food gets wasted and never reaches those who need it.

Weather shocks, due in part to climate change, are also increasingly driving hunger. Half the world’s poor grow their own food, and natural disasters like droughts and floods frequently wipe out vulnerable families’ entire food supply and income.

Read more: A hotter planet, a hungrier world ▸

But even if all these obstacles to food access were removed, the world will still need to change its agriculture practices to meet the needs of its growing population.

Where in the world is hunger the worst?

Nearly all the world’s hungry — 98 per cent — live in developing regions. Over 500 million live in Asia and the Pacific, in countries like Afghanistan and Timor-Leste, while 243 million live in sub-Saharan Africa.

The Food Security Information Network reports the worst food crises in 2017 were in northeast Nigeria, Somalia, Yemen and South Sudan, where famine was declared in two counties.

In 2018, the network expects conflict and insecurity to remain a primary driver of hunger, especially in countries including Afghanistan, the Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, South Sudan, Syria, Libya and Yemen, which is right now the world’s most dire food crisis.

Weather-related disasters, like drought, are also anticipated to be a major catalyst of hunger around the world in 2018 — but the impact will likely be greatest in West Africa and the Sahel, in places like Ethiopia, Niger, Mali, Kenya and Somalia.

What is being done to end world hunger?

Work humanitarian organisations are doing

We can only tackle world hunger effectively if we address what causes it in the first place. This means improving systems and behaviours that enable secure access, availability and use of food.

Fighting the drivers of hunger is key to Mercy Corps’ work with vulnerable communities in more than 40 countries:

- Agriculture: We connect farmers to the people and resources they need to increase production, feed their families and boost their incomes.

- Sustainability: We help communities develop plans and skills to sustainably manage their resources to improve crop and livestock production.

- Good Governance: We work with local governments and communities to develop just and inclusive policies that make it easier for people to access the resources they need to thrive.

- Women’s Empowerment: We partner with women and girls to build agency, and work to foster a cultural environment that supports women’s independence and decision-making power to earn income and feed their families.

- Health and Nutrition: We provide the resources, knowledge and skills needed to access and utilise clean water, employ hygienic practices and consume a diverse and nutritious diet.

Read more about our approach to building food security ▸

During acute crises, we provide at-risk communities with lifesaving assistance and the tools to re-establish healthy bodies and prosperous livelihoods. We help people with food, livelihood tools, and cash donations when food supplies are low or unaffordable, such as when people are displaced by conflict or natural disasters.

We also work with governments, multilateral institutions and other key stakeholders to support funding programmes and implementing policies that help stop global hunger and malnutrition and improve the lives of millions around the world.

Legislation and help from the government

After decades of underinvestment, countries have begun to reinvest in programmes to fight global hunger. The effort has built momentum over the years, culminating in 2015 when the global community came together to commit to pursuing the Sustainable Development Goals, with ending hunger as a top priority.

Private companies, NGOs, universities and academic institutions joined national governments with new agriculture and nutrition investments in response.